Juliana Koury Gaioso and Alexandra Murariu

Alexandra Murariu, a master’s student in Global Development at UiA, had the opportunity to conduct her master’s thesis research in Uganda last semester with the GENDIG scholarship, including support from the School of Women and Gender Studies at Makerere University. She spent her time mainly in Kampala but also had the opportunity to visit Jinja, Entebbe, the Equator, Murchison Falls, and Lake Mburo. Currently, she is residing in Taiwan while working and writing her master’s thesis. Alex agreed to chat with me via WhatsApp. During our conversation, we discussed her role as a researcher, the challenges she encountered during her research, and the valuable lessons she learned.

Juliana: Hi Alex, thanks for making time for this conversation. Could you start by providing an overview of your research? What is it about, and why did you choose Uganda?

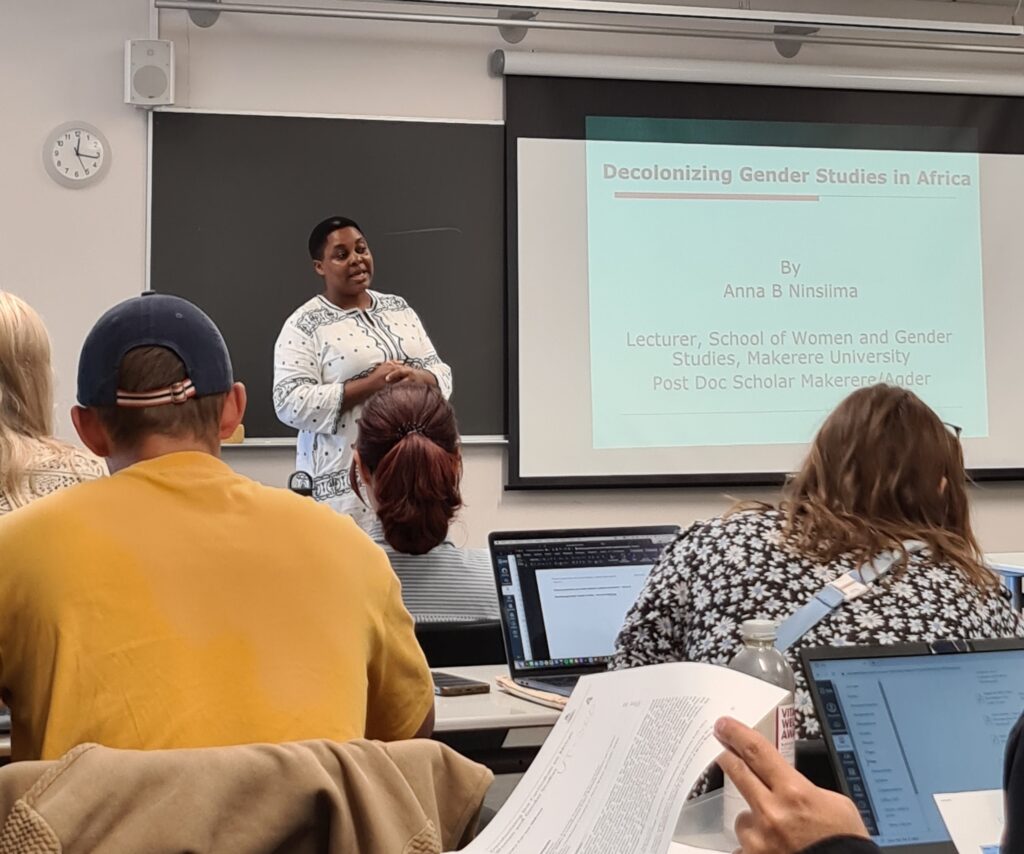

Alex: Hi! Absolutely. Thanks. My research focuses on students who are also parents, the so-called “student-parents”. This idea sparked when I read an article about some women who became pregnant during their studies and were subsequently expelled. At the same time, another article presented student-fathers as ghosts since no one seems to care about them. Unfortunately, research is scarce on this topic, which motivated me to delve into this issue. Some of my classmates, aware of my interest in Gender Studies, alerted me to the GENDIG scholarship, which led me to Uganda. Last year, it took work for me to juggle a full-time job with full-time studies, and I was constantly thinking about the challenges these students faced and wondered how parents, especially mothers, manage it all. When you don’t have children, you can sleep, study, or eat whenever and whatever you want. However, parenthood is a tremendous responsibility, which is why I wanted to explore their experiences and challenges. So far, I haven’t come across any research specific to this topic in Uganda, and even the professors there said that my research might be the first of its kind. I’m passionate about gender, education, and policies, and my findings are aimed at meaningful recommendations for policymakers and positive changes for student-parents.

Juliana: How have your experiences in Uganda influenced your understanding of gender?

Alex: Understanding gender is a complex issue. As in many parts of the world, Uganda has gender roles with distinct expectations from men and women, but traditional gender norms are also challenged. I could see that many efforts have been made and are still being made to promote gender equality, but there’s still a long way to go. Even though I focus my research on both mothers and fathers because they face different challenges, mothers still carry most of the work in Uganda. However, including both sides is crucial to work towards improving conditions for everyone. When both are better understood and supported, they can collaborate more effectively. I also considered guardians because, in my view, they share similar struggles, and the biological factor shouldn’t be the determining one. At the same time, in the second fieldwork stage, I interviewed faculty and administrators to better understand their perspectives and opinions on what can be done. I’ve learned so much from all the respondents, and I am so thankful they took the time to be part of my study.

Juliana: And what about the cross-cultural aspect?

Alex: Of course, there are plenty of differences between the Ugandan and European cultures, sometimes leading to miscommunications or misunderstandings. Finding participants was sometimes challenging, but I also received much support, especially from the students I had already interviewed, as they handed my flyers around the campus to other parents they knew. To attract participants, I sometimes had to say about the small amount of money they were receiving for their time, which is mandatory in Uganda anyway. Outside the campus, I sometimes felt that being constantly labelled a “Muzungu,” which refers to a foreigner, created a barrier. Another significant challenge I faced was the cultural differences in relation to time and the lack of punctuality. Many didn’t adhere to the agreed-upon schedule, leaving me waiting at the university from morning until evening. Some would cancel on me, while others didn’t show up as planned. It was incredibly frustrating when some said nothing about it and took extreme flexibility for granted. However, I had a valuable conversation with my supervisor, Arnhild. She raised a crucial point: when they arrived late, did I inquire if it was due to parenting responsibilities or unforeseen circumstances? It was a wake-up call for me, as I realized I had been missing a significant aspect of my research by not documenting every single one of these occurrences.

Juliana: Besides the participants not showing up, what other challenges did you encounter during your fieldwork, and how did you address them?

Alex: I had emotional moments during interviews, especially when speaking with young girls facing challenging situations. It’s difficult not to become emotionally involved when you care about the people you’re talking to. For instance, I met a younger student who got pregnant without being married during her studies. The man who got her pregnant disappeared, and her father also turned his back on her, but luckily, her mother supported her. Her case is more common than one would think, and many times, when a young, unmarried girl gets pregnant, she’s ostracized by her friends and others in the community and considered a bad influence. Their lives are not easy. For example, living with a child in the university’s hostels isn’t an option, but it’s still better than being homeless since most of them can’t afford alternatives. Some even resort to illegal abortions, and sadly, some have died as a result. Regarding fathers or guardians, I also encountered cases that impacted me deeply as they sacrificed so much to get their degrees, including being far away from their families for months or years. These experiences reminded me of the immense resilience these individuals possess, and I look at them as heroes. Witnessing their determination moved me to tears, and after a long day of emotionally charged interviews, I would return home to transcribe or work on my thesis, but exhaustion often took over. It was challenging both physically and emotionally.

Juliana: Could you share any recommendations or suggestions for future students or researchers interested in conducting fieldwork in Uganda or similar settings?

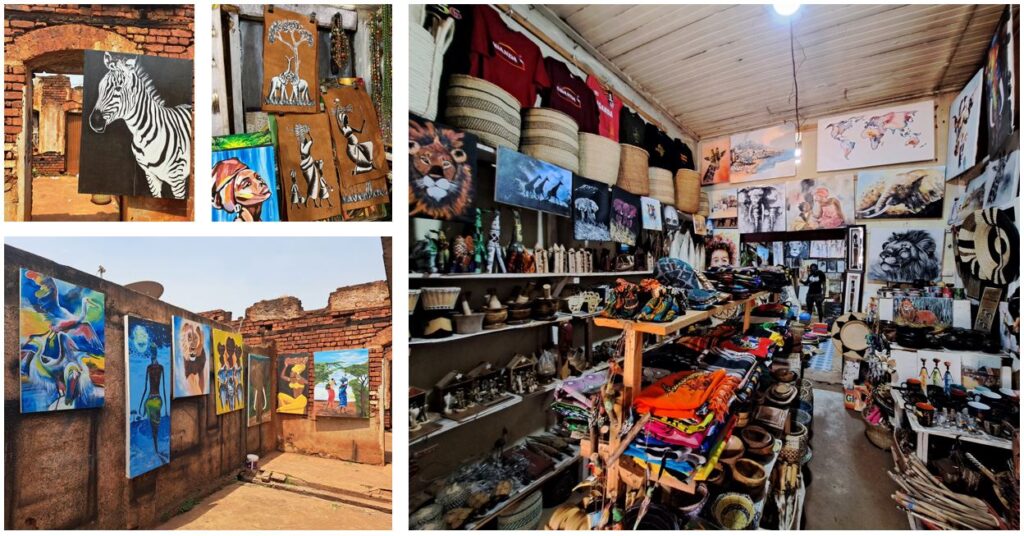

Alex: First, read in advance about the local environment and culture, and get to know them the moment you arrive there. Africa is incredibly diverse, and neighbouring countries have distinct cultures. Similarly, each country has its way of doing things in Europe, for example. Specifically in Uganda, if you go there for research, I recommend researching the cost of living because it can be way more expensive than expected, especially for a Muzungu. Be financially prepared. It is a wonderful country with unique places, so travel and interact with the locals. Also, explore the local cuisine, and don’t hesitate to try food from less touristy places. I personally loved the food and the fruit they have and was lucky enough to be there during the crickets’ season when I tried “nsenene”, a delicacy in Uganda that I loved.

Juliana: What’s the most significant lesson you’ve learned from this journey?

Alex: There are so many on my list, but I would say that I’ve learned to be more grateful, as that was the feeling I had every morning while being there. I was so grateful for all the experiences, even though they sometimes came with mixed feelings. I was grateful for making Uganda the first African country where I lived (though for only four months) and adding it as the seventh on my list. This opportunity was a great incentive and a transformative experience that highlighted the importance of gratitude despite the mixed feelings that sometimes came with it. I am grateful for having had the chance to enjoy this with my classmates, Anezka and Susanne. We shared the flat and spent so much time debating each other’s research in that living room and not only. I am grateful for being there together, for learning from and supporting each other and creating wonderful memories. I’m grateful for meeting so many lovely people (either locals, expats, or other exchange students), making friends and learning so much from them. Also, one of my best friends, Denisa, joined me for a month, and I’m grateful we had the chance to spend that time together. You know, I even had the chance to meet my classmate, Edgar, in Nairobi, whom otherwise I would not have met in person. How can I not be grateful for that?

Moreover, Uganda and my short trip to Tanzania and Kenya again proved that the world is not as bad and dangerous as portrayed. Before going there, I’d only read things like how unsafe it is, especially for a white person, how you must be home by 7 p.m. or always take an Uber to places past that hour. Of course, you must be careful, but it wasn’t as dangerous as even the locals would often say. We took boda bodas to get around the city, to get to the seamstress somewhere outside Kampala, to go shopping, or even walked to places. Always be careful but remember that this world is way better than its portrayal.

In the end, I want to say that I’m grateful for the scholarship GENDIG provided us, as I don’t think I would’ve done this without it. I hope more students will have this opportunity, as it is life-changing. Research-wise, it provides many practical skills you otherwise wouldn’t get and takes you out of your comfort zone. But that’s the beauty of it. I thank the School of Women and Gender Studies at Makerere, my mentor Ruth, and people who helped us and were so nice to us, and I thank my respondents for taking the time to be part of my research, as I know their time is so valuable. The most special thank you goes to my supervisor. A big thank you for all that!